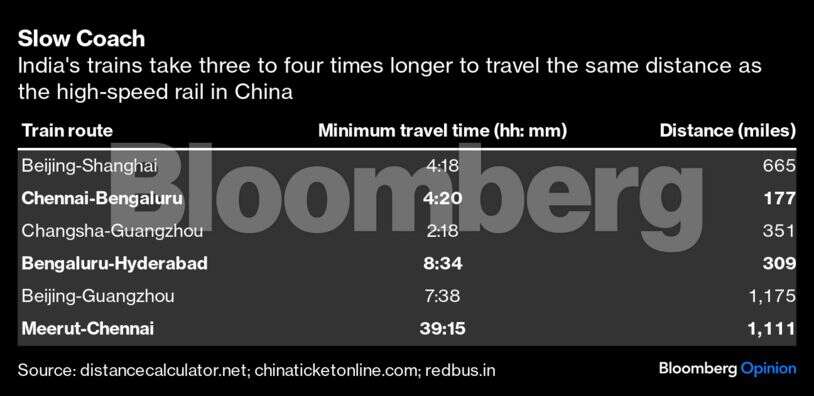

Chennai and Bengaluru, two important hubs of economic activity in southern India, are 177 miles apart. The fastest train journey between them takes four hours and 20 minutes. In the same time, you could cover the 665 miles from Beijing to Shanghai by high-speed rail. In this comparison of domestic travel lies something unexpected: the two countries’ divergent success in tapping global export markets.

Starting with the inaugural Beijing-Tianjin line in 2008, China’s high-speed rail is now a 26,000-mile network and supports a top speed of 220 miles per hour. Meanwhile, Vande Bharat Express, India’s newest and fastest passenger locomotive, is unable to accelerate to its full potential — most parts of the existing tracks won’t even allow 80 miles an hour.

A Japanese-backed bullet-train project is under construction. But it’s running late. The first route, which will cut down the travel time between Mumbai and Ahmedabad in Prime Minster Narendra Modi’s home state of Gujarat to under three hours, from more than five at present, will be operational only by August 2026. By then, China’s HSR would swell to more than 30,000 miles.

What has local train travel got to do with exports? A lot, according to Lin Tian at INSEAD in Singapore and Yue Yu at the University Of Toronto. The economics professors looked carefully at the staggered opening of new high-speed rail stations in China between 2008 and 2013 and asked a simple question: Is there a relationship between a firm’s domestic geographic integration and its embrace of international markets? Their analysis suggests that there is indeed a strong link. A one-standard-deviation increase in geographic integration leads to a 4% rise in a firm’s export revenue, driven by a 5% reduction in the unit price of exported products and a 9% increase in export volume.“The evidence was clear: Firms were not just exporting more, but they were exporting better,” the researchers write.

India’s notorious red tape and shortage of good-quality infrastructure usually get the rap for its merchandise exports not taking off the way they did in China. Cities like Bengaluru did well in software outsourcing because services exporters didn’t need roads or ports; they could even live with long and frequent power-grid outages.

While this analysis is broadly correct, it doesn’t give enough attention to transport as a tool for knowledge sharing. In their paper, Lin Tian and Yue Yu cite anecdotal testimony from 2013. The New York Times interviewed the sales manager of a garment export company based in Changsha, the capital of Hunan province in south-central China, who had increased his business trips to Guangzhou in the Pearl River Delta to once a month from twice a year to “pick up on fashion changes in style and color more quickly.” The bullet train, which covers the 350-mile journey in a little over two hours, had boosted his orders by 50%.

It is here that India has fallen behind. In services exports, skilled engineers relocated from smaller cities to Bengaluru and Hyderabad in the south and the national capital region around Delhi in the north. In finance and entertainment, they gravitated toward Mumbai. However, in goods trade, the know-how was with owner-managers. And they weren’t always to be found in large exporting clusters.

Take Meerut, once a decently sized hub of component makers in India’s landlocked north. That was before Maruti Suzuki India Ltd. created a new center of gravity around its factory on the outskirts of New Delhi in the 1990s. Meerut to Delhi was still a short train ride, but over the past two decades, the spatial contours of the industry have changed once more. Thanks to Hyundai Motor Co. and Toyota Motor Corp., the locus has moved southward, to peninsular India. Going to Chennai from Meerut by train takes 39 hours. The Beijing-Guangzhou HSR link, covering roughly the same 1,100-mile distance, squeezed travel time to eight hours — a decade ago. Nowadays, the journey takes 7 hours and 38 minutes.

No surprise then that the small and midsized industries of Meerut and other older production hubs in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh are fading. More generally, the contribution of the manufacturing sector to India’s economy has shrunk to just 13%, the lowest in more than 50 years.

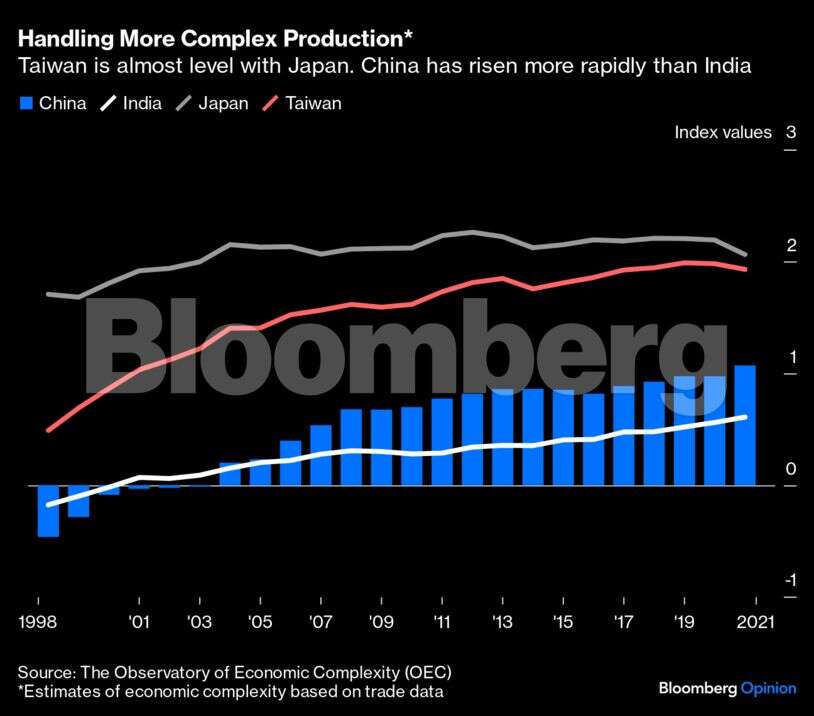

Contrast this hollowing out with Taiwan, whose own high-speed rail began service in early 2007 with a 220-mile line connecting Taipei in the north to Kaohsiung in the south. Its real benefit, though, lay in the fast link it provided to stops along the route, allowing the chip sector to expand beyond Hsinchu in the northwest, home to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Faster connectivity has done wonders for Taichung and Tainan, in the center and south of the island, respectively. TSMC’s Tainan factory, for example, hosts its most-advanced technology and has become the base for making Apple Inc. chips used in iPhones and Macs.

India’s missed opportunity may have a bearing on its future. Coming up from when it could make and sell only very simple things, China has steadily climbed the ladder of sophistication, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity, which produces annual statistics on the topic. India’s rise has been more muted. Imagine a situation where the smaller economy is trying to catch up by putting more of its youth to work in new factories. Meanwhile, China expands the spread of its manufacturing skill via the HSR network to the rust belt in the northeast of the country and to the hinterlands in the west, where labor costs are still low.

Who comes out ahead in 2030? Or 2050? China’s decline as a manufacturing powerhouse isn’t as inevitable as the consensus among analysts believes it to be.

Maglev, or magnetic levitation, has crunched the 19-mile distance from Shanghai’s airport to the city to eight minutes. The technology’s cost disadvantage — a four- to nine-fold increase over high-speed rail — put off the US. But that was nearly 20 years ago. From 2027, Japan will offer passengers the option of floating over the tracks between Tokyo and Nagoya at a maximum speed of 314 miles per hour; in 10 years, shinkansen’s Maglev version will stretch to Osaka.

By extending the technology to intercity travel, China may be able to connect its financial center with its political capital in 2 1/2 hours. China’s superior productivity may trump India’s demographic advantage.

New Delhi has gotten a few things right. At least for large firms that can keep up with onerous filing requirements, a nationwide consumption tax has made the flow of goods from one state to another smoother than before the introduction of the levy in 2017. Many new highways have been built; airlines will add 100 planes a year to their fleet in the foreseeable future. The country is meeting record peak power demand of 240 gigawatts without debilitating shortages. Smartphones and cheap data have allowed people to connect half a world away over Zoom.

Yet, all fledgling exporters intuitively know that 90% of their future wealth may come from a single serendipitous encounter. In a continent-sized economy where the first railway line arrived in 1853, trains remain the most affordable way for entrepreneurs in peripheral cities and towns to dip in and out of production centers in search of those opportunities, without sacrificing their wafer-thin margins.

Give people the option of skipping expensive hotel stays, and you’ll find them going long distances to meet prospective customers, suppliers, employees, partners — anyone who can fill a capability gap, open a new market, find a unique product or source a promising technology. Air travel is for when the outcome of a meeting is in the bag. The train is for moonshots. The first country in the world to land a spacecraft near the lunar south pole shouldn’t be taking this long to crunch intercity travel.